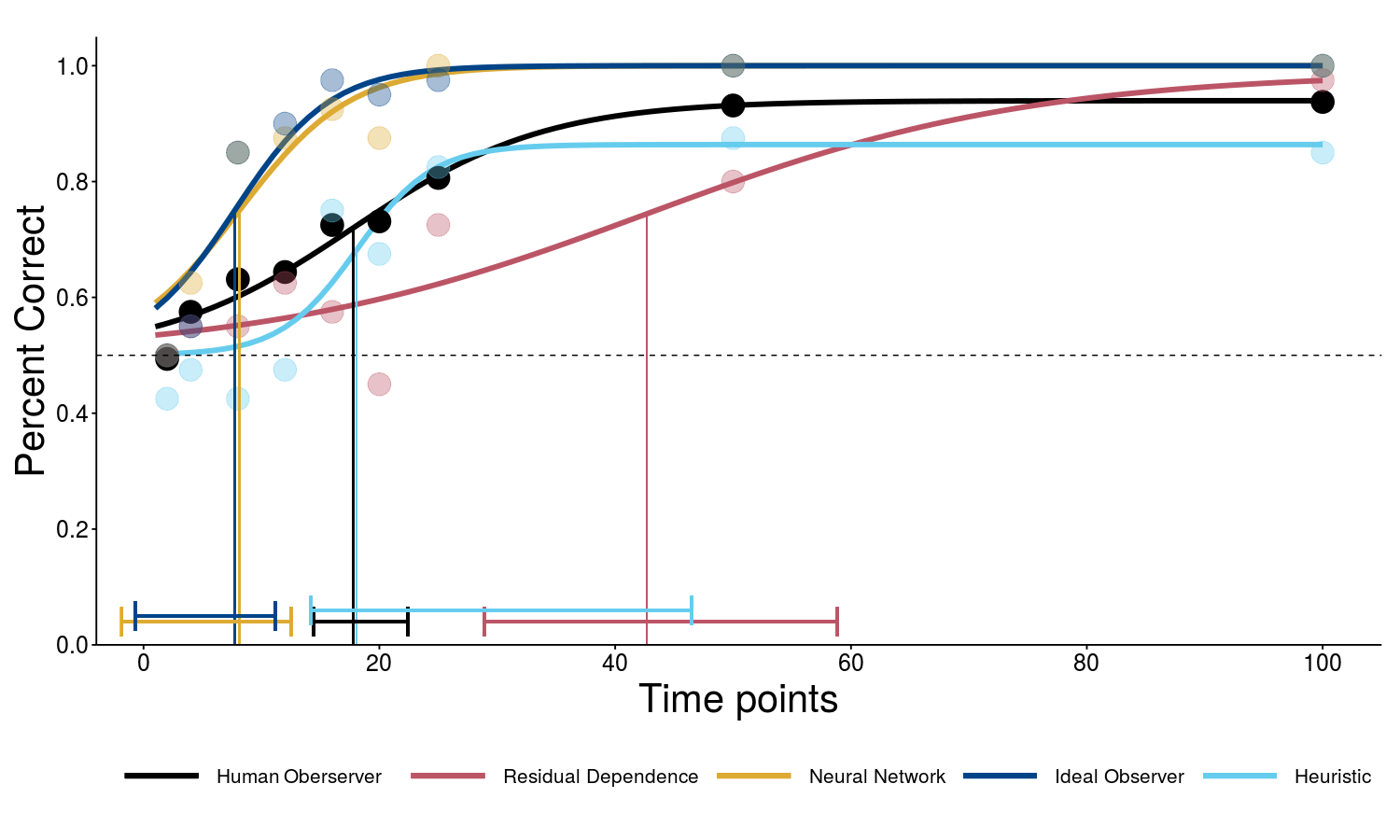

Experiments on the identification of the direction of the time series of a moving object on trajectories of different lengths. Black dots represent human accuracy pooled over all subjects. Colored dots represent different algorithms. Performance gets worse towards shorter time series. The vertical colored lines mark the 75% threshold for the psychometric fits and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals are shown at the bottom. The horizontal dashed line marks the chance accuracy (50%).

Much of the research in cognitive science and an increasing fraction of that in machine learning agree that truly intelligent behaviour requires causal representation of the world. A central research question is which behaviourally relevant input data support causal inference algorithms of human perception: what are the critical cues in complex, high-dimensional real-world data impinging on our sensory systems that our causal inference algorithms run upon?

Recent ML algorithms exploit the dependence structure of additive noise terms for inferring causal structures from observational data [ ], e.g., to detect the direction of time series; the arrow of time. This raises the question whether the subtle asymmetries between the time directions can also be perceived by humans.

We show [ ] that human observers can indeed discriminate forward and backward autoregressive motion with non-Gaussian additive independent noise, i.e., they appear sensitive to subtle asymmetries between the time directions. We employ a so-called frozen noise paradigm enabling us to compare human performance with four different recent ML algorithms. Our results suggest that all human observers use similar cues or strategies to solve the arrow of time motion discrimination task, but the human algorithm is significantly different from the three machine algorithms we compared it to.

Together with the results of an additional experiment [ ]—using classical as well as modified Michotte launching displays—we now believe that the human ability to "see causes'' is at least in our settings an early, a perceptual rather than a late, or deliberate, cognitive ability.

Another project of interest to psychology studied how to enhance human learning in spaced repetition schemes as used, e.g., in language learning [ ].